No Bank Account? No Problem. Is Your Mobile Money the Future of Credit?

Access to credit is one of the most powerful forces in an economy. It’s the invisible engine that allows a family to buy a home, a student to get an education, and an entrepreneur to turn a brilliant idea into a thriving business. It transforms aspirations into realities. Over a century ago, the United States stood at a critical juncture, developing the systems and institutions that would bring credit to the masses and fuel decades of unprecedented economic growth. Today, here in Tanzania, we find ourselves at a similar, yet profoundly different, inflection point.

While separated by a hundred years and vastly different technological landscapes, the American journey offers a fascinating mirror for our own. It provides critical lessons in what it takes to build a culture of credit from the ground up. However, the true opportunity for Tanzania lies not in imitation, but in innovation. By leveraging our unique digital strengths, Tanzania doesn’t have to follow America’s path; it has the chance to leapfrog it entirely, building a more inclusive, efficient, and equitable financial future for all its citizens.

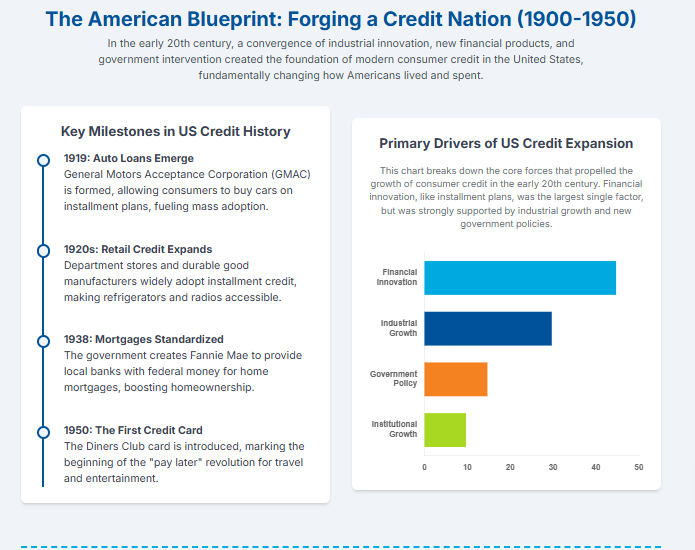

Part 1: The American Blueprint - Forging a Credit Nation

To understand where we’re going, we must first understand how we got here. Picture the United States in the early 1900s. It was a nation in flux, shifting from agrarian roots to an industrial powerhouse. Cities were booming, factories were churning out new and exciting products, and a new middle class was emerging with new desires. Yet, for the average person, finance was a local affair. Credit, if available at all, came from the corner store owner who knew your family, and it was primarily for necessities, not aspirations. The idea of borrowing money to buy something like a car was largely unthinkable.

This reality was upended by a powerful convergence of three forces:

1. The Engine of Mass Production: The single greatest catalyst was the availability of mass-produced consumer goods. Henry Ford’s Model T is the quintessential example. By 1919, a car that was once a luxury for the wealthy was rolling off the assembly line in droves. The problem was no longer supply, but affordability. The average American worker couldn’t simply pay cash. This created a powerful market vacuum: millions of people wanted to buy, but they needed a new way to pay.

2. The Spark of Financial Innovation: Into this vacuum stepped a new generation of financial pioneers. In 1919, General Motors founded the General Motors Acceptance Corporation (GMAC), a revolutionary idea dedicated to one thing: providing financing for people to buy GM cars. The "installment plan" was born. This concept was electric. It rapidly spread from automobiles to other high-value durable goods like radios, refrigerators, and washing machines. For the first time, families could acquire assets that improved their quality of life by paying for them over time.

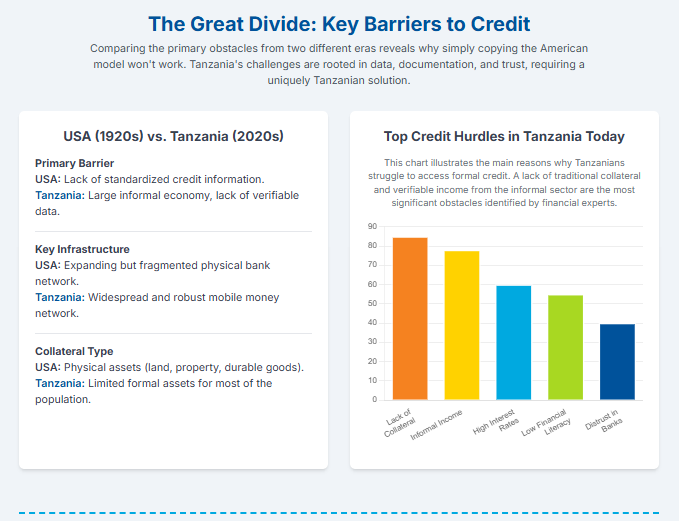

3. The Foundation of Government and Institutions: While private innovation provided the spark, government and new institutions provided the stable foundation for growth. The most critical development was the creation of a system to manage risk. In a small town, risk is managed through reputation. In a sprawling, anonymous nation, you need data. This led to the rise of the first credit bureaus, which began the slow, arduous process of centralizing information on consumer borrowing habits. This was the data revolution of its day. Furthermore, the U.S. government stepped in to standardize markets. The creation of the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) in 1938 was a landmark event. It created a national market for mortgages, providing local banks with the liquidity to lend and standardizing the terms of home loans, which ultimately made the dream of homeownership an attainable goal for millions and solidified a culture of long-term debt.

Together, these forces—industrial, financial, and institutional—wove the fabric of the modern American credit system. It took decades of painstaking, analog work, building physical bank branches, creating paper records, and slowly earning the public’s trust.

Part 2: The Tanzanian Paradox - A Digital Nation with a Credit Gap

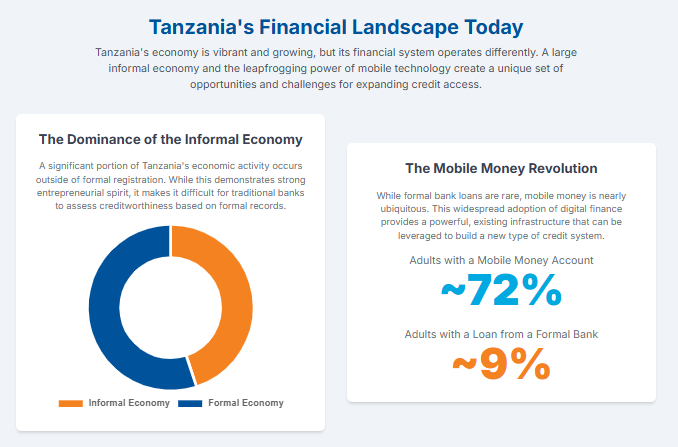

Now, let’s fast forward a century and cross the globe to Dar es Salaam. Tanzania in 2025 is a nation brimming with energy and potential. It boasts a fast-growing economy, a youthful and entrepreneurial population, and a spirit of remarkable innovation. Yet, it faces a profound paradox: it is a world leader in digital finance, but a laggard in formal credit access.

While an estimated 9% of Tanzanian adults have a loan from a formal financial institution, an astounding 72% actively use mobile money accounts. Services like M-Pesa, Tigo Pesa, and Airtel Money are not just novelties; they are the core financial infrastructure for the majority of the population. People use them daily to receive payments, pay for groceries, settle utility bills, and send money to family.

The reason for this gap lies in the very structure of our economy. A significant portion of Tanzania's economic activity—estimated to be around 45% of GDP—takes place in the "informal" sector. This doesn’t mean it isn’t real; it means it operates outside the systems of formal registration. It consists of millions of small-scale farmers, shopkeepers, motorcycle taxi drivers (bodaboda), and artisans who are the lifeblood of our communities. For a traditional bank, these individuals are financial ghosts. They lack the formal payslips, tax records, and registered business documents required to pass a conventional credit check. They have income, but no "proof" of income in a language the old system understands.

Herein lies the fundamental difference between America’s challenge and our own. The U.S. in the 1920s needed to build a financial information system from scratch. Tanzania in the 2020s already has a rich, real-time, digital financial information system—it just isn’t being used as one. The problem isn’t a lack of data; it’s a failure to translate that data into trust.

Part 3: A 21st-Century Solution - Building on a Digital Foundation

Tanzania’s path forward, then, is not to painstakingly recreate the 20th-century American model. We don’t need to focus solely on building more physical bank branches or waiting for the entire economy to formalize. We need to build a new system on the digital rails that already exist.

This new model treats a person’s mobile money transaction history as the valuable asset it is: a dynamic, real-time ledger of their economic life. This digital footprint reveals far more about an individual's financial health than a static payslip ever could. It shows their consistency of income, their spending patterns, their reliability in paying bills, and the seasonality of their cash flow. This is the "new collateral"—a collateral of data and behavior.

The pathway to unlocking this potential is a clear, multi-step process:

- Leverage Transaction Data: Fintech innovators and forward-thinking banks must partner with mobile network operators to analyze mobile money data—always with explicit user consent and robust privacy protections.

- Develop Alternative Credit Scoring: Using machine learning algorithms, these partners can build new credit scoring models. Instead of asking "What assets do you own?", these models ask "How do you manage your money?". They assess creditworthiness based on digital behavior, unlocking financial identities for millions.

- Launch Digital Micro-Loans: The journey begins with small, accessible loans. A farmer might get a 50,000 TZS loan to buy seeds, or a shop owner a 100,000 TZS loan for inventory, all applied for and delivered through a simple app. The primary goal of this first step isn't just to provide capital, but to generate a crucial data point: a successful repayment. This builds the first rung on the credit ladder.

- Bridge to the Formal Economy: With a history of successful digital repayments, individuals build a verifiable credit score. This score then acts as a bridge, allowing them to access larger, more traditional financial products. That initial micro-loan, successfully managed, becomes the key that unlocks a business expansion loan, and eventually, a mortgage from a formal bank.

This technological framework must be supported by a robust ecosystem. It requires nationwide campaigns to improve financial literacy, ensuring people understand how to use credit productively. It needs a supportive regulatory environment from the Bank of Tanzania that encourages this innovation while fiercely protecting consumers. And it relies on continued public and private investment in the digital infrastructure that forms the bedrock of this entire vision.

The United States spent fifty years building its consumer credit system with factories, filing cabinets, and interstate highways. Tanzania has the opportunity to build its system in a fraction of that time using smartphones, data analytics, and the mobile internet. By embracing our unique position, we can not only solve our credit gap but also create a blueprint for financial inclusion that will inspire nations across Africa and the world. The revolution is coming, and it will be digital.