The Tanzanian E-Commerce Paradox: Why Jumia Crashed and Local Players Survive

In the world of digital commerce, Tanzania presents a fascinating paradox. It's a nation where over 95% of the adult population uses mobile money, a sophisticated digital payment system that many Western countries might envy. With a massive, youthful population of over 70 million, it should be a fertile ground for e-commerce giants to plant their flags and reap the rewards. Yet, the landscape is littered with the ghosts of failed ventures, most notably the spectacular exit of Jumia, the "Amazon of Africa."

On November 27, 2019, Jumia ceased its e-commerce operations in Tanzania, a move that sent shockwaves through the continent's tech scene. The official line was a strategic "portfolio optimization" to focus on more profitable markets. But for anyone on the ground, the real reasons were far more complex and revealing. Jumia’s failure wasn't an indictment of Tanzania's potential, but a masterclass in what happens when a global, venture-capital-fueled model collides with local reality.

The story of e-commerce in Tanzania is not one of failure, but of a profound misunderstanding. It’s a tale that reveals why the true digital marketplace thrives not on slick apps, but in the bustling, trust-based world of WhatsApp and Instagram, and how smaller, local players have survived by understanding the unwritten rules of Tanzanian commerce.

The Ghost of Jumia: A Lesson in Market Mismatch

Jumia’s arrival in Tanzania was heralded as the dawn of a new retail era. Backed by significant funding and a pan-African ambition, it brought a model that had been proven elsewhere: a vast online marketplace, a proprietary logistics network, and a focus on aggressive customer acquisition through discounts. But this model, built for scale, shattered against three uniquely Tanzanian walls: trust, logistics, and culture.

The first and most formidable wall was trust. In a market where commerce is inherently relational, Jumia was perceived as a faceless, corporate entity. Its marketing was a barrage of promotions, failing to tell the human stories that build connection and confidence. Tanzanian consumers, wary of online scams and counterfeit goods, were not won over by discount codes. This trust deficit was starkly reflected in the payment data: a staggering 94% of Jumia’s customers opted for Cash on Delivery (COD). This wasn't a matter of convenience; it was a risk mitigation strategy. Customers needed to see, touch, and verify a product before handing over their money.

The second wall was logistics. Jumia tried to impose a centralized logistics model on a country where a standardized physical address system is largely non-existent. Last-mile delivery became a nightmare of failed attempts and endless phone calls between drivers and customers, driving up operational costs and frustrating shoppers. The company was trying to build a superhighway on a network of unpaved roads.

Finally, the entire venture was built on flawed unit economics. The "growth-at-all-costs" strategy, fueled by venture capital, was unsustainable. The high costs of acquiring customers, coupled with the immense expense of inefficient logistics and low average order values, meant the business was bleeding money on a path that had no clear route to profitability. Jumia’s exit was a painful but necessary lesson: a generic pan-African strategy is no substitute for a deeply localized one.

The Real E-Commerce: Thriving on WhatsApp and Instagram

While Jumia struggled, e-commerce in Tanzania was—and still is—booming. It just doesn't look like what you'd expect. The real marketplace lives on social media. The typical customer journey begins with discovering a product on an Instagram feed or a Facebook page, which together command millions of users in the country.

From there, the transaction moves to a direct, one-on-one conversation, usually on WhatsApp. Here, the buyer and seller negotiate the price, discuss product details, and arrange for delivery. This informal system works precisely because it solves the problems that crippled Jumia. Trust is established through direct human interaction. Logistics are handled by a vast, hyper-local network of boda-boda (motorcycle taxi) riders who know the neighborhoods intimately. Payment is made directly from one person to another via mobile money or as cash upon delivery, eliminating the perceived risk of online payment fraud.

This social commerce ecosystem isn't a bug in the system; it's the defining feature of the market. Formal platforms aren't just competing with other websites; they are competing with this deeply entrenched, trusted, and highly efficient informal network.

The Survivors' Playbook: How Local Platforms Endure

Against this challenging backdrop, a handful of formal e-commerce platforms have managed to survive and, in some cases, thrive. Their strategies, whether by design or evolution, offer a playbook on how to operate in the Tanzanian market.

- The Generalists (Zudua & Dar Shopping): Local marketplaces like Zudua.co.tz and Darshopping.co.tz have persisted where Jumia failed, likely by growing more organically and adapting their models to local conditions. They position themselves as trusted, homegrown platforms, building their brand on reliability rather than rapid, unsustainable promotions.

- The Specialists (Impala & Shopit): Players like Impala.co.tz and Shopit.co.tz have carved out defensible niches by focusing on high-trust categories like branded electronics and IT equipment. By guaranteeing authentic products from brands like Sony, HP, and Philips, they directly address the consumer's fear of counterfeits. Furthermore, they embrace local payment realities, offering a full suite of options from M-Pesa to, crucially, Pay on Delivery.

- The Trust-Builders (Spring Soko): Spring Soko operates as a multi-vendor marketplace with a clear mission: to empower local sellers and build a secure ecosystem. Its model directly confronts the trust deficit with features like requiring a customer to provide a One-Time Password (OTP) to the delivery driver, ensuring a verified handover of goods.

- The Facilitator (Jiji): The undisputed king of the classifieds space is Jiji.co.tz, which became dominant after acquiring its main rival, OLX, in 2019.The classifieds model is perfectly suited to the Tanzanian context. It doesn't try to manage payments or logistics; it simply connects buyers and sellers, who then conduct their transactions on their own terms, mirroring the dynamics of social commerce.

Cracking the Code: The Future of Tanzanian E-Commerce

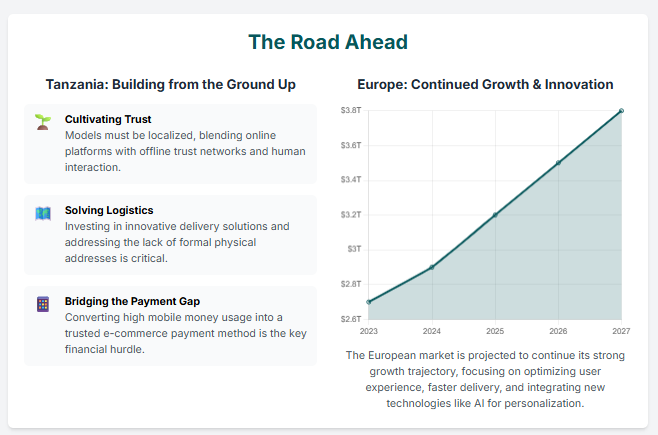

The lessons from Tanzania's e-commerce crucible are clear. Success is not about transplanting a foreign model but about building a business from the ground up with the local context in mind. For any company looking to enter or scale in this market, the strategy must be built on a few core commandments.

First, prioritize trust above all else. This means rigorous seller verification, transparent customer reviews, and strictly enforced return policies. Second, embrace an asset-light and flexible logistics model. Partner with local couriers and boda-boda networks and use a network of pick-up points to solve the last-mile delivery challenge. Third, build the entire payment system around mobile money and Cash on Delivery. COD is not a temporary crutch; it is a long-term trust-building feature.

Finally, and most importantly, localize everything. The user interface must be simple, mobile-first, and available in Swahili. Marketing must be relational, telling the human stories of local sellers and satisfied customers.

The next major test for the market is on the horizon. The Kenyan e-commerce platform Kilimall has announced its planned entry into Tanzania, and its strategy appears to have been designed with Jumia’s failure in mind. By starting with an asset-light logistics model and focusing on partnering with small local vendors, it is showing a more patient, nuanced approach. Its success or failure will be a key indicator of the market's evolution.

Tanzania is not a graveyard for e-commerce. It is a high-friction, high-potential environment that demands respect for local culture, an obsession with building trust, and a creative approach to solving on-the-ground challenges. The opportunity is immense, but it belongs to those who understand that in Tanzania, commerce is, and will remain for the foreseeable future, deeply human.